In honor of the Fling’s 71st Reunion

The first Fling Reunion was held June 18, 1950 at Loves Lookout in Jacksonville, TX, with 60 members present. The picnic lunch celebrated Charles R. Fling’s 67th birthday. Someone suggested the family hold a reunion annually, and Granddaddy invited the Family to be his guests at Starke Park in Sequin, TX July 4, 1951. These annual reunions are one reason the Fling family have remained close throughout the years.

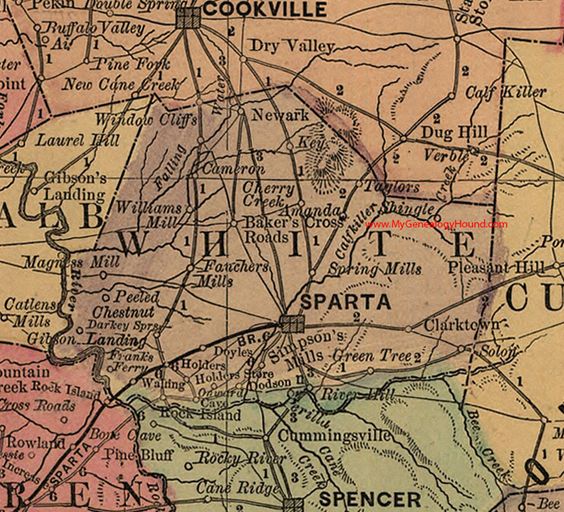

The map above shows Sparta, TN as well as Cherry Creek and Dug Hill (discussed below).

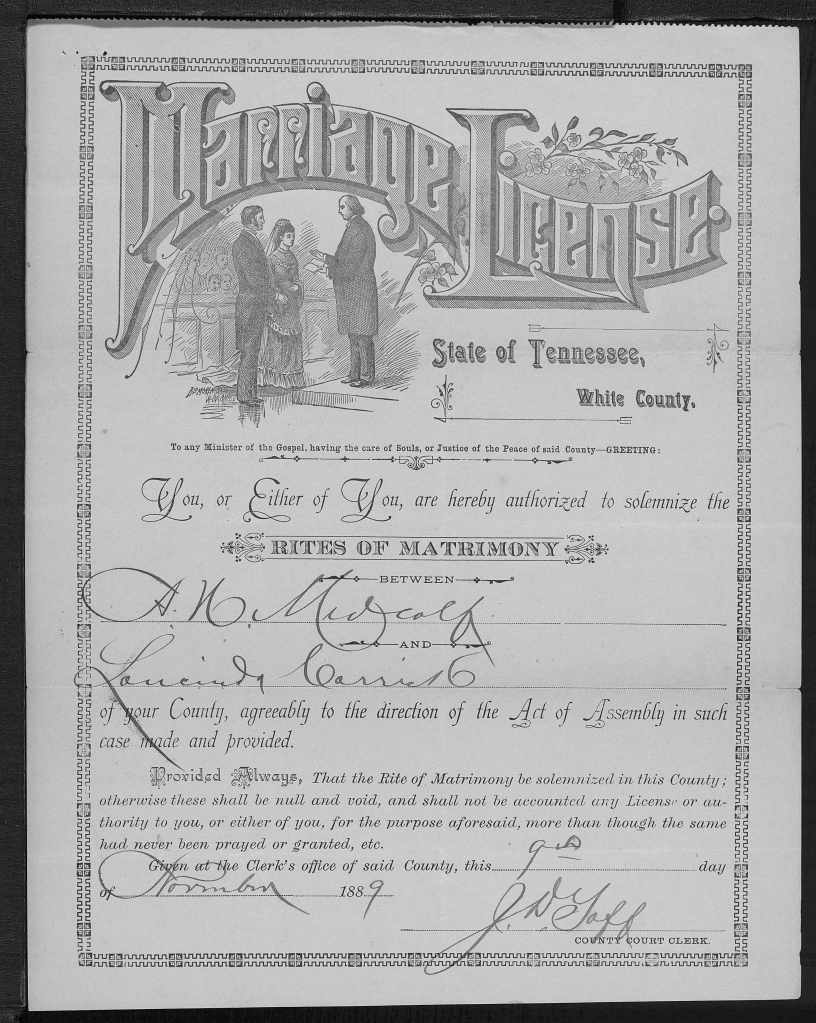

These are the stories of Loucinda Carrick, known to family as Granny Lou, mother to Mama Fling, and her family.

Loucinda Carrick was born in or near Sparta, in White County, Tennessee to George Dawson Carrick and Martha Glenn Sims. Her mother’s parents were William Gilmore Sims and Lucinda Mae Glenn. William Sim’s first cousin, also named William Gilmore Simms (but who added an extra “M” in his last name), was a famous Southern author of the 1800s, and his portrait hangs in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

William Gilmore Simms

(first cousin to Loucinda’s maternal grandfather)

Left motherless at two, this William was raised by his maternal grandmother as his father fought the Creek tribe of Native Americans and served under Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812’s famous Battle of New Orleans. His grandmother told him stories of the Revolutionary War, which she had lived through, and those stories inspired his love of history. William began writing poetry by age eight, and ultimately became a prolific writer specializing in books about the South. Edgar Allen Poe considered him a friend, and called him the best novelist American had yet produced. Simms’s “History of South Carolina” was used as the textbook for that state’s history courses for most of the 20th century. He collected perhaps the finest library of historic manuscripts in the South, with Revolutionary War-era manuscripts and more than 10,000 books — but all were lost when stragglers from Sherman’s Army burned down Simms’ plantation home and everything in it. Impoverished after the war, he was not forgotten. Most of his books have been digitized and are available through print-on-demand.

Lucinda Mae Glenn (Loucinda Carrick’s maternal grandmother)

Lucinda Glenn Sim’s husband William died in 1855, when she was 40 years old. He left her well-off, with plenty of land along Cherry Creek in White County, Tennessee. A few years after he died, in 1859, she built the home pictured above. (She left the home to her youngest son, Perry, and it is Perry and his family who are pictured above). One winter day in February 1864, her home was visited by Union soldiers, who requisitioned her horses, carts and wagons to use for the grim business of picking up the bodies of those who had been killed in the Battle of Dug Hill the day before. (Cherry Creek and Dug Hill are both shown in the map above.) Dug Hill was the only official battle of the Civil War fought in Sparta, though fighting, robbery or worse were part of daily life during that time. Middle Tennessee was split between Union and Confederate sympathizers, though after the fall of Nashville then-Colonel Ulysses S. Grant held the area. Despite being under Union control, few men were left in Sparta to protect the residents from guerrillas and bushwhackers from both sides who roamed the area.

The guerrillas shot, stole and murdered in these hills and woods with impunity, making every-day life a challenge to all, including for Lucinda and her family.

It came to a head on the afternoon of Feb. 22, 1864, when Military Governor and future president Andrew Johnson sent a Col. Stokes to rid Sparta of Rebels. Stokes loudly asserted that he would do the job, offering no quarter to any Confederates he may find, promising to kill rather than capture the Rebels caught in his snare. Stokes planned to address the citizens of the area in a speech later that day, so he sent out a band of 80-100 soldiers to clear the woods of enemy forces and ensure the festivities would not be interrupted by gunfire. While he was setting up for his address, his soldiers rode straight into an ambush. The Confederate forces in the area had heard Stokes’ plans, and came up with one of their own. They hid out and waited for the Federal soldiers’ path to take them to the area of Dug Out Hill, a narrow road between the Cumberland mountains and CalfKiller River, where immense boulders, scrub cedars and laurels lined the path and created ideal hiding places. As Union Private Clark, with the Advance Guard of the Union’s 5th Tennessee Calvary’s rode near Dug Out Hill, he noticed fresh horse tracks in the road. Looking up, he spotted two Confederate soldiers mounted on fine steeds, guns resting across their saddles.

“Boys,” Clark yelled, “yonder stand two Confederates. Suppose we get ’em”! With that he raised his gun and began shooting. The Rebels started galloping and led the advance guard towards the trap they had set. When the Feds entered the narrow pass, the Rebels emerged from their hiding spots and began firing. The Union soldiers were surrounded, and as the volley of shots rang out from all directions the soldiers were scattering everywhere, Rebels in hot pursuit for any that seemed to be escaping. Riderless horses stampeded in all directions, adding to the chaos. All that were found or surrendered were killed the spot, as the Rebels decided if Stokes would give them no quarter, they would do the same.

Blissfully unaware that his men were even then fighting for their lives, Col. Stokes laid the pages of his speech out on the podium in front of the church, cleared his throat, and was just beginning to speak when a tattered Federal soldier burst through the doors — missing his shoes, hat and coat — and stammered “Colonel, the damn rebels have attacked the regiment and killed them all. I’m the only one left to tell the tale!” That turned out not to be true, as several more survived, but there was such pandemonium each survivor felt sure he was the only one. It does not appear that any of our family fought that day. However, a detachment of the Feds went to the Lucinda’s home (pictured above) and took her horses, carts and wagons to use in carrying away the dead soldiers’ bodies. Despite that, for years after, Sparta residents found skeletons in the nearby woods.

Photo of CalfKiller River by Brian Stansberry – own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15024981

Martha Glenn Sims (Loucinda Carrick’s mother)

Although the Battle of Dug Hill was the only official battle fought in Sparta, violence was ever-present. Loucinda Carrick’s mother and Lucinda Sim’s daughter — Martha Glenn Sims — had at least one fright of her own. She went with a boy named Jeff Snodgrass (likely a relative, as Martha’s grandmother was Martha Snodgrass) to a meeting at the Cherry Creek Presbyterian church, near the Sim’s house. Several bushwhackers were present, as was one of their sisters, Diana Bradley. Jeff Snodgrass was Diana’s former sweetheart. Diana did not take being rejected by Jeff in favor of Martha well, to say the least. When the meeting was over, Jeff started off with Martha and a friend named Arva Cameron. As they were leaving, Diana called out to him — “Take back what you said about me!” Jeff turned to look back at her and when he did she shot him in the chest and, to make sure he was good and truly dead (or so as not to be shown up by his sister), her brother ran up and shot Jeff again as he fell. Fearing Diana and her brothers meant to kill Martha and Arva as well, they ran away. Before the bushwhackers could go after them, they found trouble of their own. The boy Diana was with that day was shot by another bystander in the neck. Bleeding profusely, Diana rushed him off to try to find a doctor to stop the bleeding and save his life.

In the meantime, with everyone fearing more trouble, no one was brave enough to retrieve Jeff’s body, so it lay there until all day, until an old slave finally was sent to retrieve him and bring his body home. There was essentially no law at this time, so Diana was never arrested for the crime. After the war she went West with the bushwhackers. Martha married another neighbor, George Dawson Carrick, and the rest is history.

Martha’s sister Mary also had at least one story of note to tell during this time. A neighbor, Mrs. Bledsoe, fell sick and feared she didn’t have long to live. She wrote to her son, fighting for the Confederacy, and asked him to come home to see her one last time. Mary knew that the soldier was at the Bledsoe home, and as she was outside near the home she noticed a group of Yankees riding towards the Bledsoe home, no doubt on a mission to capture the Rebel. Mary hitched up her skirt and started running, trying to outrun the horses. Spectators that day say she soon was only a few feet in front of the charging Yankees, and they were sure she would fall under the horses’s feet and be trampled at any time. Mary stayed upright, however, and the commotion warned Bledsoe and gave him time to try to escape. He jumped on his horse and sped off, but, seeing that the Yanks were going to catch up to him, he leapt off his horse and ran into a large briar patch, where he hoped to hide. Instead, he became entangled in the undergrowth and ultimately was killed. It is said that his wife had to pick the briars out of his face before she buried him. [Credit for these stories goes to research conducted by Coral Williams, who wrote “The Heritage of Daniel Haston/Legends & Stories of White County, TN” based on both research and interviews with those in the area.]

George Dawson (Loucinda’s paternal Great-Grandfather)

George Dawson is said to have run “Dawson’s stand” in the early 1810s – 1850s in White County, TN, and he served as Postmaster General at Dawson Store in the area between 1826-1828 and 1837-1843. He and his wife – Nancy Mosby – are the parents not only of Emily Dawson (Loucinda’s paternal grandmother), and Susan Dawson (George Dawson Carrick’s step-mother), but also Hero of the Texas War of Independence Capt. Nicholas Mosby Dawson, whose stories are told below. In addition, Nancy Mosby’s sister was mother to the three Eastland men mentioned in the story of Texas’ War of Independence, below.

Emily Dawson (Loucinda’s paternal Grandmother)

Emily Dawson died, likely due to a childbirth complication, only a few weeks her son George Dawson Carrick was born. Emily’s brother, Capt. Nicholas Mosby Dawson, was a hero of the Texas War of Independence, as were her three cousins — Nicholas, William and Thomas Eastland. History tends to capture the stories of the men, a situation I would love to remedy. But for now I know nothing more of Emily than that she died soon after giving birth to her second son, and that she had a famous sibling, two years her junior, who left for Texas shortly after she passed away. I would like to think the two were close, but I have no way of knowing. Her younger sister, Susan, later became the step-mother to her son.

Capt. Nicholas Mosby Dawson and the Dawson cousins – Nicholas, William & Thomas Eastland

The Dawson and Eastland children were born in Kentucky, but soon moved with their parents to White County, TN. As young men they became entranced with the idea of Texas, and all four decided to move there, even though the land was part of Mexico. The Eastland brothers and their families moved first, in 1834, and Nicholas Dawson followed the next year. Mexico was giving away land to settlers willing to brave the Native Americans who, not surprisingly, had not taken kindly to their land being taken over by others. The Eastland and Nicholas Dawson all settled in LaGrange when it was still part of Mexico. For a few years the cousins volunteered to fight the Native Americans, and soon volunteered to fight the Mexicans to win independence for Texas. Nicholas and at least two of the Eastland cousins fought in several battles, including the Battle of San Jacinto which was the decisive battle that won Texas its independence. Nicholas was 2nd Lt. for Company B of the Texas Volunteers, and then captain of a militia unit in 1840 during an Indian campaign in which is now Mitchell County. When the Mexicans invaded Texas in 1842, he quickly signed up to fight again, taking his 16-year-old nephew (Nicholas Eastland’s son) and about 14 others from LaGrange with him, and joining up with others along the way until his had 52 men under his command.

They were marching towards San Antonio, to join up with the Texans who were already there, attempting to recapture the city. They unfortunately ended up trapped between the Texas forces and a group of lance-wielding Mexican Dragoons along the Salado Creek.

Dawson laid out the options to his men — fall back four miles, or shelter in the nearby mesquite and fight it out. Despite the odds, their decision to make a stand was finalized after hearing the words of old frontiersman Zadock Wood, who said, “We have marched a long way to meet the enemy, and I do not intend to return without meeting them. I had rather die than retreat.” With that, the men voted to remain and fight, and fight they did. At first they had the upper hand, gunning down the Mexicans with their sabers despite being outnumbered three-to-one. Then the crack of a canon broke through the noise, and fragments of trees rained down on their heads, and the Texans’ hearts sunk with the realization that artillery they hadn’t seen had been wheeled into place above them, and that artillery made all the difference. Soon more than a dozen of the Texans were dead, along with most of their horses. Cherokee snipers working with the Mexicans were picking off the survivors. Though it soon was clear they were done for, the Texans continued to fight valiantly for as long as they were alive. Finally, a few made a break for it and bravely and with a lot of luck on their side rode straight through the enemy to safety on the other side. In the end, 15 of the 53 were captured as prisoners, many of whom soon died, and only two escaped. All of the rest, including Nicholas and his nephew, died that day along the creek.

Later, their bodies were dug up and reburied at Monument Hill State Park, overlooking the Colorado River, near LaGrange. [Credit for much of the information in this story goes to Austin photojournalist and Texas history lover Ben Friberg.]

Perhaps Dawson’s fighting spirit was no surprise to his parents, based on the snippet of a news article I found from Fayette County (home to LaGrange). It talks of three “nice young men” sent to jail for horse stealing, one of them being Capt. Nicholas Dawson’s youngest brother, George. Nicholas was also sent to jail, for supplying the prisoners “with the means of escaping from jail.” Apparently they were not kept in jail for long.

The Eastland Cousins

The cousins — the Eastland brothers — all also fought for Texas, without much more luck than Dawson. William Mosby Eastland had left the saw mill and lumber business he had begun in LaGrange and went to serve as first lieutenant of the First Division of Volunteers under Col. John H. Moore in the campaign against the Waco and Tehauacana Indians from July 25 to Sept. 15, 1835. In 1838 he was awarded land for having participated in the storming and capture of Bexar after the Siege of Bexar as part of the Texas War of Independence, as well as the Battle of San Jacinto. On Dec. 7, 1836 President Sam Houston, upon the recommendation of the Texas Sec. of War, nominated William Eastland as Captain of a company for Gonzales County in a battalion of mounted riflemen. After General Rafael Vasquez unexpectedly invaded San Antonio on March 5, 1842 and a few months later General Adrian Woll made a surprise raid and captured many prominent men attending a District Court in the area, carrying them to Mexico as prisoners, Sam Houston gathered volunteers to retaliate by sending an army to invade Mexico. For unknown reasons, however, once they reached the Rio Grande River they were ordered disbanded. Three hundred of the men, surprised and displeased, ignored the orders and continued marching into Mexico. Captain Eastland and 25 men in his company fought in a fierce battle in Mier, Mexico not far from the Rio Grande River on Christmas evening, 1842. The Texans, though greatly outnumbered, were victorious. However, the Mexicans were reinforced the next day and, through a ruse, left the Texans in a position such that there was nothing left for them to do but surrender. They were made to march towards Mexican prisons when, on Feb. 11, 1843, they overpowered their guards and escaped to the mountains. Many died of starvation, though four made it back to Texas. The others eventually were recaptured and returned to Salado — including Capt. Eastland. Santa Ana gave orders to execute every tenth men as punishment for the escape. The prisoners were blindfolded and forced to draw from a clay jar of 159 white beans and 17 black beans, knowing that anyone who drew a black bean would be executed. Captain Eastland was the first and only officer to draw a black bean and, thus, a death sentence. A few days later, he along with 16 others were blindfolded and shot in the back, thrown in a single trench and buried. Five years later they were exhumed and reburied along with those who were killed in Dawson’s massacre, on Monument Hill in LaGrange. Eastland County, TX is named for William Mosby Eastland.

Nicholas Washington Eastland lost both his son Robert (in Dawson’s Massacre) and his son Charles to the War, in addition to his cousin Nicholas Dawson, his brother William (discussed above) and his brother Thomas, who died as a prisoner of war in Mexico, as well as his good friend and Texas hero James Walker Fannin (massacred at Goliad). Nicholas Eastland served as the first County Judge of Fayette County (1838-1844), was Chairman of the Board of Land Commissioners, and served as Probate Judge. He was Representative from Bastrop County in 1863. He had a lot of property, and had a sawmill operated by slaves near the town of Bastrop.

George Dawson Carrick (Loucinda’s Father)

George Dawson Carrick’s mother, Emily Dawson, died only a few weeks after his birth, presumably as a result of childbirth although there are no records of her cause of death. I suspect his aunt, Susan Dawson, was a part of his life early on, as she was a younger sister to Emily, his mother, and married to his father’s brother. After his father’s brother — Moses Carrick — died in 1843 Susan married George’s father and officially became his stepmother (but by that time George was 13).

George, a slave owner, fought for the Confederates during the Civil War. He joined Captain J.H. Snodgrass’ Company A 25th Regiment of the Tennessee Company as a private Sgt. Major July 25, 1861. He later transferred to Company D, 13th Tennessee Calvary, where he was a private. He is said to have fought in Readyville, TN, and to have fought again Union General Verbage in Saltville, VA and General Sherman in Georgia, as well as in North and South Carolina. Some sources say he was discharged in 1862, others that he was discharged in Jan. 1864.

George married Martha Sims on Oct. 6, 1868 and they had six children: William Montgomery, John Addison, Loucinda (Mama Fling’s mother), Frank, George Dawson Jr. and Emily. After Martha died in 1890, when Loucinda was 18 and a new bride, George and his three boys (each of whom married one of three Little sisters)– along with Loucinda and her new husband, Anthony Houston Metcalf– moved to Northeast Texas and then to Harmon County, Oklahoma. (It’s unclear if they moved, or if the state boundaries moved around them.) He originally took two of his freed slaves with him (Matt and her daughter Allie) but neighbors in the new territory forced them to return to Tennessee. George’s youngest daughter, Emily, did not stay long in Texas, and is the only one of the family to have moved back to Sparta, TN. A photo of Emily (Loucinda’s baby sister) and her family are below.

Loucinda Carrick (Granny Lou)

Loucinda married at 17, to a neighbor — Anthony Hugh Metcalf — whose first wife (Loucinda’s cousin Mary Snodgrass) had died. He was 37 years old, with four children, so Loucinda stepped into a ready-made family. Mary Fling, her first child, was born 8 Nov. 1891 and named by her half-brother “Bevy” after his own recently departed mother. Soon she was “Sis” to her siblings, Mama to her children and Mama Fling to her grand children, great grandchildren and many others in the Turney community. Sometime between 1891 and 1894 the family moved to Wilbarger, TX. Wilbarger, in northeast TX, had been buffalo hunting grounds of the Comanches until the 1870s, and Indian hostilities caused few settlers to settle there until 1878. In 1886 Fort Worth and Denver City Railroad built a train going into the area, and encouraged immigration. This may be why the Carricks and Metcalfs settled there, around this time. However, after a peaceful and prosperous decade in the 1880s, and soon after our family moved to the area, times changed. Many farmers and ranchers suffered reversals in the 1890s, so the Carrick’s/Metcalfs didn’t move to the area at the best of times. At some point the family moved to Oklahoma, not far to the north (or the shifting boundary between Texas and Oklahoma changed the state designation of their land, it’s unclear.) Loucinda’s child born in 1898 was born in Wilbarger, TX but by the time of Joe Bailey’s birth in 1901 the family had settled in Gould, Harmon County, Oklahoma. They remained in Harmon County, OK for the rest of her life.

Granny Lou and her husband grew cotton, which was then spun into thread and woven into cotton fabric, which Granny Lou used to make her girls’ dresses and her boys’ shirts and pants.

Mama Fling loved it when she was able to visit with her mother. The photo below was made sometime around 1939. Loucinda is in the front left, sitting next to her are Eddie Glen Wheeler, Billy Shepherd, Burton, and C.L. Wheeler. Mama Fling is at the end behind C.L., with Granddaddy sitting behind Eddie Glen.

I scour the internet, Ancestry.com and the other genealogy sites as well as the Salt Lake City Family History library for information on our family. I would love to hear from anyone who has more stories to tell, or photos to share. I will scan them and return them, and add the information to the story for future generations to tell of the men and women who came before us, and whose blood runs through our veins.